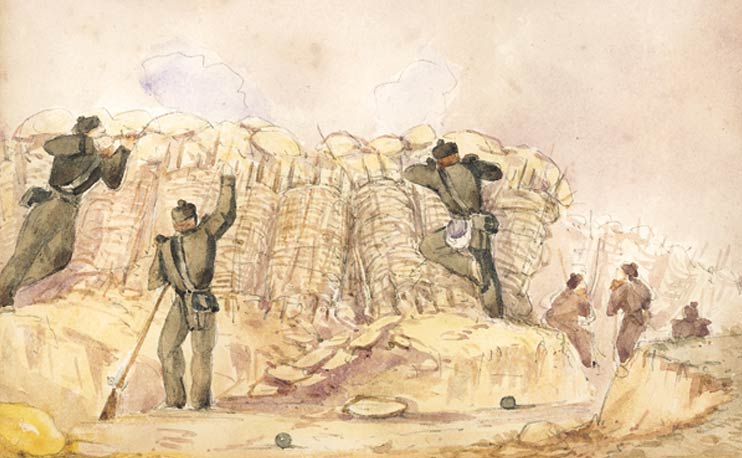

Watercolour of a Rifleman in the Crimea by Lt the Hon. H.H. Clifford VC.

This object is one of 19 exquisite watercolours in the Museum’s collection painted by Lieutenant the Hon. H.H. Clifford of The Rifle Brigade, who was awarded a Victoria Cross for his gallantry during the Crimean War (1854-6). This particular watercolour is of a Rifleman in The Rifle Brigade looking as he no doubt looked most probably during the siege of Sebastopol.

All Clifford’s watercolours are of scenes and people painted during the war, thus they provide an admirable impression of the circumstances that prevailed in the very inhospitable climate and conditions of the Crimea.

Clifford’s watercolours show that not only was Clifford a very brave officer, but also a very talented artist.

All 19 watercolours are on display in the Crimean War section on the first floor of the Museum.

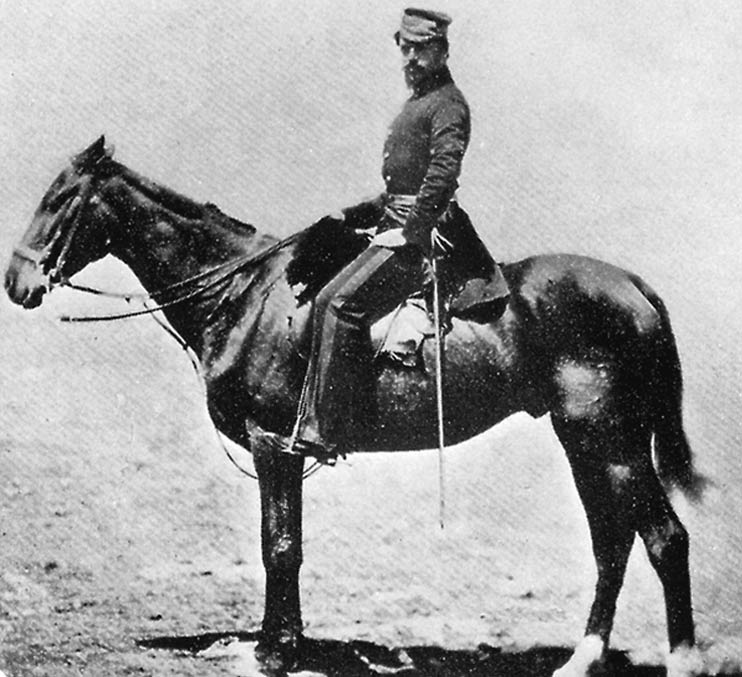

Lieutenant the Hon. H.H. Clifford VC (Later Major-General Sir Henry Clifford VC KCMG CB)

Lieutenant Henry Clifford was born at Irnham Hall, Lincolnshire, on 12 September 1826, the third son of the 7th Baron (Lord) Clifford of Chudleigh, and educated at Stonyhurst College. After purchasing his commission, he served with the 1st Battalion, The Rifle Brigade (1 RB) in 1846–7 and 1852–3 during the South African (Kaffir) wars. On return to England, the Commanding Officer of 1 RB, Colonel Buller, was appointed a brigade commander in The Light Division during the Crimean War and Lieutenant Clifford was appointed his ADC.

Lieutenant the Hon. H.H. Clifford at Sebastopol.

Clifford was present at the battles of the Alma and at Balaclava before taking part at the Battle of Inkerman on 5 November 1854. His subsequent VC citation, published in the Supplement to The London Gazette of 24 February 1857, is brief, stating: ‘For conspicuous courage at the Battle of Inkerman, in leading a charge and killing one of the enemy with his sword, disabling another, and saving the life of a soldier.’

Watercolour of Inkermann by Lt the Hon H.H. Clifford VC.

Clifford provided a fuller account of the action in a letter written on the day after the battle. ‘Dear Relations and Friends’, he wrote:

Yesterday morning at daybreak, fire of Musketry was heard to our extreme right; we turned out 18 Officers and 656 Sergeants, Drummers, Rank and file of the 88th and 77th Regt, all we had at our Brigade in Camp (the remainder being in the Trenches), and under the command of Sir G. Brown [commander of The Light Division] and General Buller marched off in the direction of the firing, which became more and more serious, cannon opening and shell bursting in the lines of the Division which is about a quarter of a mile on our right.

On reaching the ground of the 2nd Division it was evident from the roll of musketry the enemy was in great force and had driven back our Picquets. Most unfortunately the weather was very foggy, and we could only be guided by the sound of the firing. When about 50 yards from the crest of the hill in our front, over which the attack was being made, we formed into line, the 88th Regiment on the right and the 77th Regiment on the left; we brought our right up so that our left might rest on a large and deep ravine. We moved quickly on in the direction of the shots, which from the way they whistled past, and the great report made by the discharge, I was sure must be very close.

On reaching the left brow of the hill, I saw the enemy in great numbers in our front, about 15 yards from us; it was a moment or two before I could make General Buller believe that they were Russians. ‘In God’s name,’ I said, ‘fix bayonets and charge.’ He gave the order and in another moment we were hand to hand with them. Our line was not long enough to prevent the Russians outflanking our left, which was unperceived by the 77th, who rushed on, with the exception of about a dozen, who, struck by the force on our left and who saw me taking out my revolver, halted with me.

‘Come on,’ I said, ‘my lads!’ and the brave fellows dashed in amongst the astonished Russians, bayoneting them in every direction. One of the bullets in my revolver had partly come out and prevented it revolving and I could not get it off. The Russians fired their pieces within a few yards of my head, but none touched me. I drew my sword and cut off one man’s arm who was in the act of bayoneting me and a second seeing it, turned round and was in the act of running out of my way, when I hit him over the back of the neck and laid him dead at my feet. About 15 of them threw down their arms and gave themselves up and the remainder ran back and fell into the hands of the 77th returning from the splendid charge they had made and were killed or taken prisoners.

Out of the small party with me (12), 6 men were killed and 3 wounded, so my escape was wonderful.

The way in which Clifford conducted himself caught the eye of General Brown, who was later to write of Clifford, that he was ‘universally admitted to be one of the most gallant and most promising young officers in the Army’. After promotion to Captain on 29 December 1854, he became Deputy Assistant Quarter Master General of The Light Division, continuing to serve in the Crimea until the end of the war, by which time he had been appointed Brevet Major. In addition to the VC, he was awarded the French Legion of Honour and the Order of Medjidie – the Turkish equivalent to the Legion of Honour.

After the Crimean War, Clifford served in China (1857–8) as Assistant Adjutant General during the Second China War, returning to England with the rank of Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel. Further staff appointments followed, with the award of a CB on 2 June 1869 and promotion to Major-General in 1877. During the South African (Zulu) War of 1879 he commanded the lines of communication. He was mentioned in despatches and awarded a KCMG on 19 December 1879. In 1882 he was appointed to command Eastern District at Colchester, but was diagnosed with cancer and obliged to retire. He died at the family home, Ugbrooke Park, Chudleigh, in Devon, aged 56, on 12 April 1883.

Watercolour of the Advanced Trench by Lt the Hon H.H. Clifford.